A consumer electronics company used 718H mold steel to build a mobile phone housing mold (for PC+ABS flame-retardant material). After only 1,000 molding shots, scratches appeared on the plastic parts, forcing a three-day production line shutdown and incurring a repair cost exceeding approximately $7,150. This case directly highlights the hidden risks of improper selection of mold materials and underscores the critical role of scientific selection in achieving production efficiency and cost control. This content is compiled from our practical experience in mold steel selection projects and is provided for reference.

The Cost of Choosing the Wrong Material: 15% Slower Cooling and a Mold That “Strikes” After 1,000 Shots

As a commonly used mold steel, 718H has performance shortcomings that can be magnified in specific scenarios. Its thermal conductivity is lower than that of NAK80, which increases mold cooling time by about 15%. Depending on differences in mold structure (such as wall thickness and cooling channel design), the actual cooling time can increase by approximately 15–20%, extending the production cycle and reducing output per unit time.

Even more challenging is corrosion resistance. In the injection molding of flame-retardant PC+ABS, chlorine-containing components in the resin gradually corrode the surface of 718H, leading to cavity wear and, eventually, scratches on the molded parts. In the above case, failure after 1,000 shots is not an isolated incident; another company we worked with also experienced delayed delivery of their first batch of orders due to similar issues.

How to Choose Among S136, NAK80 and 718H? Real Application Scenarios Behind the Industry Rule of Thumb

The rule of thumb “for mirror finish > 50,000 shots choose S136; for 30,000–50,000 shots choose NAK80; for large-volume non-mirror parts choose 718H” actually reflects a balance of requirements in different scenarios:

S136: A typical application is injection molds for medical syringes. These molds must withstand more than 50,000 shots, resist corrosion from alcohol disinfection, and achieve a mirror surface finish with Ra 0.02 µm or better. In this case, the high cleanliness of S136 (sulfur content < 0.005%) becomes a critical advantage.

NAK80: Remote control housings in the home appliance industry commonly use this material. For small- to medium-batch production of 30,000–50,000 shots, its pre-hardened condition (HRC 38–42) allows mirror surfaces to be machined directly. At the same time, the material cost is about 30% lower than that of S136, giving it a strong cost-performance ratio.

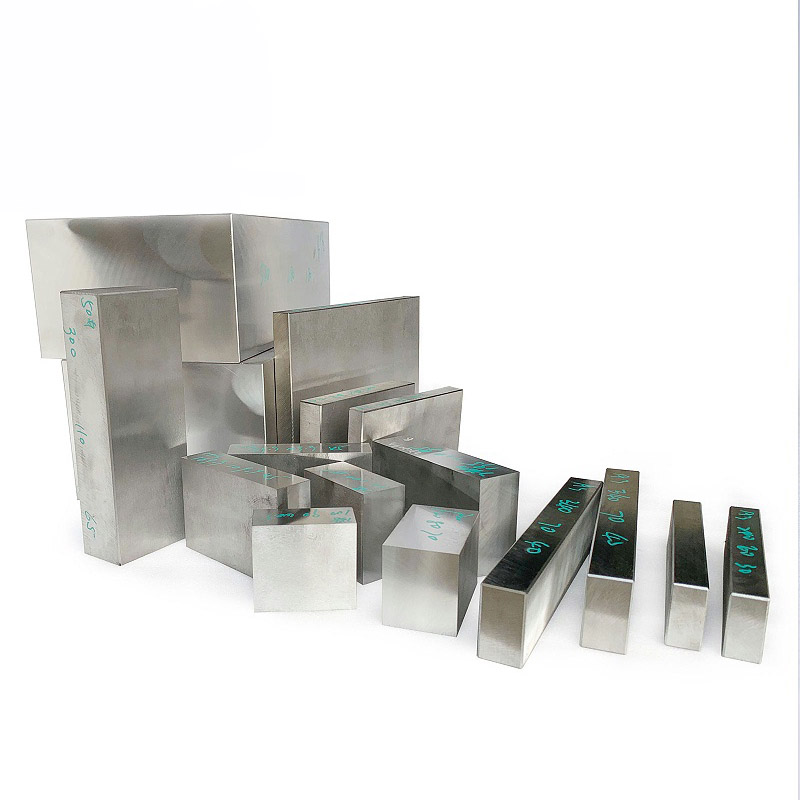

718H: Automotive door panel molds (length over 1.5 m) or large home appliance housing molds often require large-size, non-mirror, high-volume production (100,000 shots or more). In such cases, the hardenability of 718H (which can be hardened through sections up to about 200 mm in diameter) and its good machinability are significant advantages, helping reduce the manufacturing cost of large molds.

Deep Dive into Special Scenarios: Is Tool Wear with S136 Really 50% Higher? Who Performs More Stably in High-Temperature Molding?

Although S136 offers excellent performance, its machining challenges must be addressed in advance. Tool wear when machining S136 can be about 50% higher than with NAK80. The core reasons lie in its material hardness (HRC 50–55 after quenching) and alloy composition (around 13% chromium and 1% molybdenum). Higher hardness increases cutting forces, while carbides formed by alloy elements accelerate tool abrasion.

One precision mold shop reported that, after switching to ultra-fine-grain cemented carbide tools (such as WC–Co alloys with about 10% cobalt) and reducing feed rate by 15%, tool life increased by 40%. As a result, their monthly tooling cost dropped from approximately $2,860 to about $1,710.

In high-temperature injection molding scenarios (for example, PA66 with 30% glass fiber, molding temperature 280–300 °C), differences in heat resistance become very obvious. S136 shows better thermal stability, maintaining about 90% of its hardness at 200 °C, compared with about 80% for NAK80 and about 75% for 718H. This can extend mold life by roughly 20% in terms of the number of shots. By contrast, 718H tends to develop thermal fatigue cracks under sustained high temperatures. It should therefore be paired with reinforced cooling channel designs (e.g., increasing the channel diameter by around 2 mm) to mitigate the issue.

Conclusion

The core logic of mold material selection can still follow the common rule of thumb, but it must be combined with detailed application conditions: for mirror finish > 50,000 shots use S136 (the first choice for medical and highly corrosive environments); for 30,000–50,000 shots use NAK80 (the cost-effective choice for small- to medium-batch production); and for large-volume, non-mirror parts use 718H (the economical choice for large molds). At the same time, potential hidden costs must not be ignored: 718H requires surface nitriding when it comes into contact with corrosive materials. In contrast, S136 requires a well-planned machining strategy to prevent tool cost from spiraling out of control.

- Before material selection: Clearly define required mold life (number of shots), surface finish requirements, and the materials to be molded (including corrosive components).

- When machining S136: Use ultra-fine-grain cemented carbide tools and reduce feed rate by about 15% to balance efficiency and tool life.

- In cost calculations: Include the full life-cycle cost of material, machining, and downstream maintenance and repairs, rather than looking only at initial material prices.